Today’s blog post is the sixteenth in a series, the transcription of Nimrod Headington’s 1852 journal, Trip to California.

In his journal Nimrod Headington details his 1852 voyage from New York to San Francisco and his search for gold in California. [1] [2]

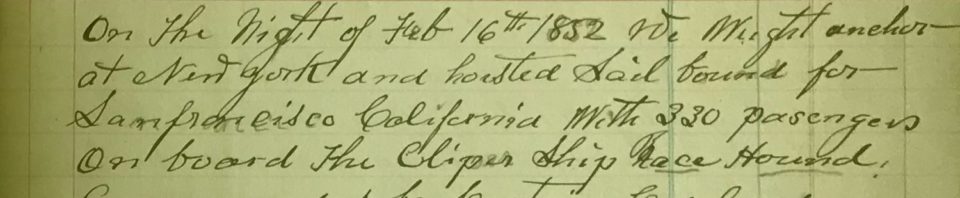

Nimrod, with several others from Knox County, Ohio, set sail from New York on 16 February 1852, traveling on the clipper ship Racehound. After 5 months at sea, rounding Cape Horn during the night of 4 May, and docking at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Valparaiso, Chile, they finally reached their destination, San Francisco, on 18 July 1852.

In today’s blog post, Nimrod begins his search for gold in California. I am repeating a little from the last post to set the scene.

July 18th. This morning when we got up, we were right close to the land. Just as the sun came up, a pilot came on board to pilot us into port. We passed through the Golden Gate at 11 o’clock and dropped anchor. We had to pay one dollar to be taken on shore, as they would not allow our ship’s boats to land our passengers. One of them attempted to go but had to come back. The rules of the port had to be complied with. We landed at the Pacific Wharf and took dinner at the Howard House, for which we paid fifty cents.

At 4 o’clock we went on board the river steamer Brighton for Sacramento and landed the next morning at 8 o’clock. Here we stopped at the Globe Hotel and remained there until the next day. Here we took the stage for Marysville and landed there at 4 o’clock in the afternoon and stopped at the Eagle Hotel. Our bills were 50 cents per meal and nothing for the lodging.

The next morning we took the stage again for Dobbins Ranch, which was 25 miles from Marysville, for which we paid four dollars each. We landed there just as the sun was setting. We had to pay one dollar for a meal.

The next morning we started out on foot, bound for Frenchman’s Bar on the Uba River. The road was very rough and hilly, and we had our blankets and luggage to carry. We came very near giving out. We had been to sea so long and having no exercise that were not in very good trim for traveling on foot. I was more fleshy heavy than I ever was in my life—and consequently short to breath.

When we got to the ranch, we put up at the house of John Higgins. We inquired of him the prospect for mining, and he made us believe that it was excellent. We asked him the price of boarding, and he told us ten dollars a week in advance. So we paid him ten dollars each for a week’s board, and then bought a pick and shovel, for which we paid five dollars each. Feeling very tired, we did not start out that day.

The next we shouldered our picks and shovels and pans and started out, but after digging several holes and washing the dirt, we could find nothing that looked like gold. The next two days we attended with the same kind of success. After a search of three days in vain, we concluded that this kind of work would not do. We should soon be minus what little money we had left. So we determined to hire by the month, as wages was good. So myself and one of my company went to a steam mill owned by an old Chilean named Lameis, where we had no trouble in getting employment of a hundred dollars a month.

He set my partner to driving oxen teams made up of the wildest kinds of Mexican cattle that did not know gee, haw, nor anything else and had to be lassoed every morning to get the yoke on them. He kept 3 or 4 Mexican men for that purpose. We went to work, but we did not stay long, as they did not give us enough to eat. And what was there the dogs would not eat without the dog was starving. When we went to the table, the boy that waited on the table would come around and lay a dirty looking cake at each plate and say, “One hombre, one bret.” And this was all we could get. At the end of seven days, we could stand it no longer, and we called on the old man for a settlement. He paid us off very promptly, and we left him alone to enjoy his dirty hash.

We then went back to Frenchman’s Bar, where we bought a share in a fluming company that was [searching] the bed of the river, for which we paid two hundred dollars down and agreed to pay four hundred more when they got it out the claim. So we worked on this way for two months. But before we got the water all dammed off, there was not work for us all. So I left them and went to Dry Creek, distance of 15 miles, for the purpose of taking up some claims then but could find none worth taking. But I stayed there some three weeks and worked by the day at four dollars a day.

While I was there, the news came to me that our river investment was a total failure. We had lost our money and hard work. I set down and studied the matter all over, and finally I came to the conclusion to go to Sierras old diggings about 50 miles up the mountains and at the base of Table Mountain—or more properly Sierra Nevada Mountain on the east side of Slate Creek. On leaving Dry Creek, I left the 2 men, Braddock and Durbin, with whom I had doubled the cape and with whom I had been partners since we landed in California. And I never met them again while in the state.

The country up here in the Sierra Nevada mountains is very rough—so much so that wagons cannot get up here. Everything is brought up here by pack trains. Trains of mules with pack saddles on will come up, 50 or 60 in a train, all loaded with provisions or something that the miners have to use. Each mule will carry from 2 to 3 hundred pounds. A man goes before on a horse with a bell on, and the mules will follow, one right behind the other. Sometimes the train is half a mile long. A Mexican follows behind to see that no mule drops out of the train or loses his load.

These pack trains are all owned and operated by Mexicans. You can hear them when they get within ten miles of us, coming down the mountain on the west side of Slate Creek swearing at the mules in Spanish. Their mule talk is hepo mulo sacare camacho.

There was a cabin close to our cabin that had a parrot, and that parrot would always hear the mule train coming before anybody would know of it, and it would begin to holler hepo mulo. Then in about 6 or 7 hours the train would arrive in camp with its cargo. [3]

To be continued…

I would love to have heard that parrot! Hilarious! Nimrod’s account gives us a vivid description of the conditions he encountered and so far his search for gold seems rather difficult.

I will post Nimrod’s journal in increments, but not necessarily every week.

[1] Nimrod Headington at the age of 24, set sail from New York in February 1852, bound for San Francisco, California, to join the gold rush and to hopefully make his fortune. The Panama Canal had not been built at that time and he sailed around the tip of South America to reach the California coast. Nimrod Headington kept a diary of his 1852 journey and in 1905 he made a hand-written copy for his daughter Thetis O. Tate. This hand-written copy was eventually passed down to Nimrod’s great-great-granddaughter, Karen (Liffring) Hill (1955-2010). Karen was a book editor and during the last two years of her life she transcribed Nimrod’s journal. Nimrod’s journal, Trip to California, documents his travels between February of 1852 and spring of 1853.

[2] Nimrod Headington (1827-1913) was the son of Nicholas (1790-1856) and Ruth (Phillips) (1794-1865) Headington. He was born in Mt. Vernon, Knox County, Ohio, on 5 August 1827 and married Mary Ann McDonald (1829-1855) in Delaware County, Ohio, in 1849. Nimrod moved to Portland, Jay County, Indiana, by 1860 and during the Civil War served in the 34th Indiana Infantry as a Colonel, Lieutenant Colonel, and Major. Nimrod died 7 January 1913 and is buried in Green Park Cemetery, Portland. Nimrod Headington is my fourth great-granduncle, the brother of my fourth great-grandfather, William Headington (1815-1879).

[3] Nimrod Headington’s journal, transcription, and photos courtesy of Ross Hill, 2019, used with permission.