by Nimrod Headington

As transcribed by Karen Liffring in 2009

Note by Karen Miller Bennett: Nimrod Headington was born in Mt. Vernon, Knox County, Ohio, on 5 August 1827, the son of Nicholas (1790-1856) and Ruth (Phillips) (1794-1865) Headington. Nimrod married Mary Ann McDonald (1829-1855) in Delaware County, Ohio, in 1849 and they had a son a year later. Despite the fact that he had just started a family, Nimrod took off for California in February of 1852, hoping to stake his claim on a profitable gold mine. Like so many others, he hoped to strike it rich. In February of 1852 he traveled to New York, where he boarded the ship Race Hound and set sail for San Francisco. To get to the west coast they had to sail all the way around the tip of South America because this was before the construction of the Panama Canal. This was evidently a good way to get to California from the east coast.

Nimrod Headington (1827-1913)

Nimrod kept a journal documenting his journey by ship to California and of his time in the California gold fields, panning for gold, spaning the time between February 1852 and spring 1853. Nimrod’s great-great-granddaughter, the late Karen (Liffring), acquired Nimrod’s original handwritten journal from her father John Liffring. The journal has been in the Liffring family since 1905, when Nimrod made a hand-written a copy for his daughter Thetis O. Tate. Karen (Liffring), who was a book editor, died of cancer in 2010, at age 55. During the last two years of her life she transcribed Nimrod’s journal. Karen’s husband passed her transcription on to me and gave me permission to post it here. I originally posted the journal as a series of blog posts but the whole journal is also on this page. I have made a few minor spelling edits to the journal.

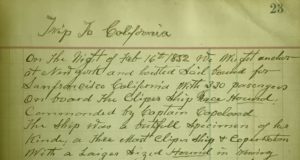

Nimrod Headington Journal, 1852, p.1

Nimrod Headington and his family moved to Portland, Jay County, Indiana, by 1860. He served in the 34th Indiana Infantry during the Civil War as a Colonel, Lieutenant Colonel, and Major. Nimrod died 7 January 1913 and is buried in Green Park Cemetery, Portland. Nimrod Headington is my fourth great-granduncle, the brother of my fourth great-grandfather, William Headington (1815-1879).

Nimrod Headington’s 1852 Journal, TRIP TO CALIFORNIA:

START OF THE TRIP

On the night of February 16th, 1852, we weighed anchor at New York and hoisted sail bound for San Francisco, California, with 330 passengers on board the clipper ship Race Hound. Commanded by Captain Copeland, the ship was a beautiful specimen of her kind: a three-mast clipper ship and copper bottom with a larger-sized hound in running position trimmed in gold on her bow.

February 17: we were under full sail and headed southeast and ran 13 knots per hour. The sea was quite rough, which made many of the passengers sea sick—some of them moaning as if in great pain, others vomiting, while a few others were laughing at their distress. As for myself, I escaped being seasick but felt somewhat distressed to see so many in distress. You could hear all kinds of remarks—some praying, some wishing they had never started. One poor fellow said, “If I was at home with my mother, I would stay there!”

February 18: The wind continued from the same direction and increasing every hour. The sea became very rough and the waves ran high, and occasionally a spray would dash over the side or bow of the ship, wetting those on deck all over. Then those that escaped would roar with laughter while those who got soaked would hunt for dry clothing.

The wind and the weather continued about the same until Saturday, February 19th, when we struck the trade winds. The wind changed and came from the west, and the sea ran down, and the passengers began to recover from their seasickness.

Sunday came, and it was a beautiful day. The sun shown so brightly on the deep blue water. No land in sight. It was warm and pleasant on deck, and everyone that was able to crawl was on deck. We had some notebooks, and we enjoyed the day in singing, making little speeches, and telling stories. There were quite a number of good singers and some musicians in our company, several violins, and some horns.

About eight o’clock that night, the wind changed to the northwest and blowed tremendous hard at ten o’clock. Our top mast and main [topgallant] mast was carried away by the storm. This left us in a very bad condition. The ship presented a horrible and pitiful-looking spectacle. Many of our passengers were considerably frightened, and I will not say that I felt at all easy over our situation. I made it a point to watch and converse with the sailors. They are so very harshly treated by the ship’s officers that they are glad to talk to anyone who will talk kindly to them, and when I could see that they were not frightened, it made me feel better, as I was not seasick any. I had good opportunities to talk with them when they were not busy.

This storm continued until Wednesday, the 25th, when it cleared up and was pleasant, but the sea waves ran high for several hours. The sailors all hands went to work, taking down the broken spars and ropes and preparing to erect new ones.

February 26: a Mrs. Bresler, the wife of a merchant of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, died. She was on her way to join her husband, who had gone to California a few months before. The funeral service was led by the ship’s captain, and she was buried the same day. There being no minister on board, it is the duty of the captain to officiate. He read the 15th chapter of Corinthians and a few of us gathered around the corpse as it lay on the plank, ready to be lowered into the sea and sang “Jesus, Lover of My Soul.” This was a sad sight for those who had never been to sea.

February 27: The sea has run down. The day is pleasant and almost calm, which very moves in our favor—being dismasted. It gave the sailors a chance to erect new masts and spars.

February 28: Two of the ship’s crew got to fighting, and the people on board crowded around. The fighters brought all on one side of the ship until they came very near capsizing us. The captain cried out to trim ship, and a rush was made for the other side, and soon the ship was all right.

MARCH 1852

Sunday, March 1: This does not appear like a Sabbath day to me. All hands working all day putting up masts and spars and passengers engaged in all kind of amusements—some playing cards, dice, or checkers, while others were reading or singing. It is anything to kill time.

March 2: Masts all up again, and we now are under full sail again, heading southeast and running 12 knots an hour in latitude 23°15’. It is quite warm so that a number of the passengers slept on deck.

The next day we struck trade winds again in latitude 20°34’. We had good sailing and smooth sea, which is very acceptable after being in a storm and seasick for so many days.

The next day, the passengers began to grumble about not getting enough to eat. The captain was waited on and notified of the condition of things in the galley kitchen, but he paid no heed to our complaint. So under the circumstances, we formed a board of health, and the next evening, we gathered on deck and proceeded to elect officers, making Captain Copeland president, Mr. John Gomd vice president, and L.D. Shelden secretary, and a committee of six to see that the rations were properly cooked and at the proper time and to see that the decks were kept clean and to report to the doctor if any were sick and needed medicine.

Friday, March 5: Fair winds and plenty of it. We headed south by east, running 14 knots per hour in latitude 14°12’. The wind continued to blow from the same direction until Sunday, March 7th, when the wind changed to northwest and continued from that direction for four days and nights. This morning finds us in latitude 4°30’. We came in sight of another vessel off our lee bow, which seemed to be heading right toward us and soon came up in plain sight, and when about two miles off, she hoisted her colors. Then up went the Stars and Stripes on our gallant ship. She came nearer and nearer until within speaking distance. Our captain came out with his speaking trumpet and hailed the other ship, saying, “Where are you from? How many days out? Where are you bound for?” And she answered from Calio, “40 days out and bound for Hamburg.” She was a Spanish bark. We gave them three cheers, and our colors dropped, and soon we were out of sight.

The next morning, it rained powerful hard. The wind went down, and the sea was calm all day. The next day, we sighted another ship light astern. There being little or no wind, she could not run up to us. The next morning, she was still in sight. Our captain, being anxious to speak to her, set back sails and at eight o’clock a light breeze struck up. We hoisted our colors, and in a minute the beautiful Stars and Stripes were up on the other ship. This was a beautiful sight to see—an American ship plowing her way through the blue water toward us. She soon came up to us, and our captain lowered a lifeboat and four sailors to row and went on board the other ship. What his business was we did not know, but we thought perhaps as we were then getting very short [on food] and on allowance. And were afraid that we should run out entirely. This ship was The Marian of New York bound for Rio de Janeiro.

March 13: Today we crossed the equator. Four hours after crossing the line, we had finer winds and good sailing. We came in sight of another ship but not close enough to speak. The winds increased, and we are running at a rapid rate. The passengers are all merry on account of such fine sailing and fine weather. When the captain took the sun’s altitude the next day at noon, we were in latitude 5°29’ south latitude. The winds continued from the same direction. The captain began to be afraid of running ashore. He went aloft and saw on our lee bow land. And he immediately came down and changed our course, and we are now running south by east running 10 knots an hour.

The ship’s doctor—we had on board a Dr. Morgan of Philadelphia—had laid in a fine supply of liquors and had it all marked Castor Oil, pretending that it was for the passengers as medical supplies, but some of the stevedores, whose business it is to get provisions and water out of the hold found out that the vessels were filled with cherry brandy of the best kind, and they broke into the caskets and handed out the liquor by the bucketful, and such a drunken set of sailors probably never was seen on board of a ship. All the stevedores, steward’s cooks, and sailors and some of the passengers were drunk. The next day, the captain found out where they got their liquor, and he sent the stevedores down into the hold and had all the caskets marked Castor Oil hoisted up on deck and then rolled it all into the sea.

The next day was very pleasant, and some of the passengers climbed up into the rigging, and the sailors thought it a good time to have some fun, and they followed them up and tied them fast to the rigging. Some of the passengers were too supple and got down without being caught.

Sunday came, and oh, what a beautiful day! We were then in latitude 18°15’, and while I was eating my breakfast, some one of the passengers cried out, “Breakers ahead!” The mate cursed him and told the man he was a damn fool, but he went aloft to see, and there he saw rock on every side. He was not slow coming down, and he called out, “All hands on deck!” to warn the ship. We ran within 50 feet of two rocks on our starboard side and could see a number more on the larboard side. Had it been in the night, we should have been smashed to pieces and gone to the bottom of the sea, but we got off safely, and we were soon out of sight of those rocks, and I hope we shall not encounter another such school of rocks.

The next day it was calm until evening, when the wind set in from the northwest and blew very hard so that we had to reef sail.

BRAZIL

Thursday fine weather and good sailing in latitude 20°14’. We came in sight of the Brazilian Mountains. We amused ourselves by looking at them all day, as we had not seen land for 30 days.

These mountains are very high and can be seen a great distance from off the sea. The mountains are covered with low bushy trees. Thousands of wild cattle can be seen feeding in the mountains, by the aid of the spyglass, and all kinds of wild animals.

March 24: We came in sight of Rio, and the light at Rio de Janeiro. The wind grew so strong that we had to tack ship and stand out to sea because we could not reach the port before dark. No vessels are allowed to enter or depart from this port after the sun goes down.

The next morning it was almost a calm, but we headed for port. At four o’clock we passed the first Fort. They hailed us from the fort, saying, “Where are you from and how many days out?” Our captain answered, “From New York, 39 days out.” In five minutes one of the custom house officers was on board of our ship, and he ordered the captain to let go anchor or the second fort would fire into us. The captain paid no attention to the officer, and when we got opposite the second fort, they cried out, “Cast your anchor immediately!” The anchor was let loose. If it had not been done, they would have fired into our ship and perhaps sunk us, as the custom of this port is to allow no foreign vessel to pass the second fort without a special permit from the first fort and from the custom house office.

A guard boat is stationed halfway between the fort and the city to prevent passengers from landing or smuggling anything to or from our ship. The custom house officer examined the ship’s papers and inquired about the health of the passengers and crew and whether we had any sickness on board since we left the port at New York and if any had died. As we had only had one death and all was well, he left us well satisfied for us to land. But previous to our landing at this port, we had prepared a petition to the American consul at this place, asking him to aid us in chartering another vessel to take part of our passengers, as we were suffering for want of room and ventilation.

As soon as the anchor was dropped, the captain gave orders that none of us should go ashore until the next morning. He thought to visit the consul first and arrange things to suit himself, but we beat his game easy, for we had some long heads in our crowd. About the time the sun set in the west and the shades of night set in, a small boat manned by two Portuguese came along the side of our ship, and without the knowledge of our captain, we lowered a man by the name of Abott from the state of Maine down into the boat by the aid of a rope and told the men to take him ashore as fast as possible. He was soon on shore and at the office of the consul armed with our petition setting forth our grievances. It being late Saturday evening, the consul told Mr. Abott to come to his office on Monday morning at ten o’clock, and at the same time he wrote a note for Mr. Abott to hand to our captain, and as the note was not sealed, he read it was a notice to the captain to appear at the same hour.

The next morning, Sunday, the captain was preparing to go on shore with his [lady] when Mr. Abott stepped up to him and handed him the note from the consul. Oh, but he was surprised! He asked Abott where he got the note and was told “at the office of the American consul.” He asked Abott if he had not seen his order that no one should go on shore until Sunday morning. Abott answered, saying, “Captain your ship is not laden with cattle, but with free-born American citizens, who have some rights that you

are bound to respect.”

Sunday in Rio de Janeiro is a day of sporting, horse racing, bull fighting, etc. I went ashore with some others with the intention of going to church, but instead of seeing people going to church, then we saw all kinds of business going on. Loading and unloading ships, cart men hurrying to and from ships, and hundreds of Negroes carrying sacks of coffee on their heads from the wharf onto the ships, and all on a run.

The stores and saloons were all open. Some saloons filled with native Portuguese and some crowded with Negroes. The inhabitants of this city are a badly mixed race of people: Two-thirds of the city are Guinea Negroes black as black can be, and their dress consists of nothing more than a breech clout, no hat, no shoes. Their hide looks like the hide of an elephant. We saw one of those poor creatures cruelly whipped on one of the piers that extended out into the bay by his master, who took him by the back of the neck and his breech clout and jammed his head on the plank and stomped with his feet. Then let him up and went at him again with a piece of sugar cane about two inches thick and five feet long and split the cane into a thousand pieces over the poor fellow’s head. The Negro got up and walked away muttering something in the Portuguese language that we could not understand. I tell you it made my blood boil, but we dare not interfere, as we were in a foreign land and among strangers.

The manner of feeding those poor slaves is hardly as good as we feed hogs. We were watching the loading and unloading of a ship at the same time. The ship was loaded with shelled corn in sacks from New York and was loading to return with coffee, and the Negroes would go up one gangplank with a sack of coffee on their heads and come down another plank with a sack of shelled corn, thus loading and unloading all at the same time.

It was about the noon hour, and we wanted to see them fed presently. Four Negroes came with large buckets on their heads and sat them down on the wharf, and the working men began to gather around and stick their dirty hands into the buckets and began to eat of the horrible-looking stuff. We could not tell what it was, but it looked like wheat bran and beans about half-cooked. They ate it like it was good, but I could not think it was very palatable. Then the manner in which it was prepared and served was horrible.

The principal coin used here is a large copper coin call a Dump, worth 2-1/2 cents. The silver coin—a milreis, worth about 56 cents. These two coins do nearly all the business of the city and is the money of the realm.

I went to see the market. It was a great sight. All kinds of fruits and vegetables, such as green beans, peas, cabbage, turnips, potatoes and green corn, fowls and fishes and shrimps and all kinds of animals for sale. I saw a great many curious things, but of all that I saw to excite my curiosity, most was an old woman sitting by the wayside that had claws instead of hands and ears like a hound.

But I must now relate what happened at the office of the American consul. The captain and Mr. Abott met at the appointed hour, and after hearing what each party had to say, the consul said that another ship must be chartered and forty of our passengers should be taken off. The captain being short of funds immediately advertised for a loan of eighteen thousand milreis to pay the expense of another vessel.

The old ship Prince de Johnville was in the port undergoing repairs, and the captain made arrangements with her to carry 40 of our passengers to San Francisco. He had to pay $200 for each passenger. We left one man in the hospital. Our head steward and wife and one sailor left us, and our head cook. We remained eight days in this port, and on the morning of the 5th of April, we weighed anchor and attempted to sail out of this port, but the captain did not understand the rule of the port. We did not get out that day. This rule is that vessels leaving must obtain from the fort next to the city a password and that password must be given at the outer fort to show that all is right, and if they have not the password, they cannot go out.

When we got opposite the last fort, the hailed us for the password. The captain did not know what they wanted and kept on. Then a blank shot was fired from the fort, and in half a minute, a shot was fired through our rigging. The anchor was dropped in quick time, and the captain lowered a life boat and went to the fort to see what was wanted. He was then informed what was required, and with four sailors to row his life boat, he went back to the first fort to get his password, and by the time he returned, the tide was setting in, and we had to hoist anchor and float back into the harbor. The next day, we attempted to run out again, but the tide set in too soon, and we could not get out. The next day, tried it again but with the same success, only we came very near running on the rocks. The office of the American consul is in plain sight of the entrance to this harbor, and with the aid of his glass could see all that was happening to us. So he sent orders to our captain not to weigh anchor again until he got a steamer to tow us out of the harbor. Only a few rods from us, we saw a Brigg run afoul of a ledge of rocks that knocked a hole in her bottom, and she sank in five minutes. A captain and two sailors were lost.

April 9: On Friday, April the 9th early in the morning, we were towed out in fine style and soon had a fine breeze and by night out of sight of Rio de Janeiro and the main land.

TO THE CAPE

The next day, we had fair winds and fair weather. We headed southwest by west and were running 10 knots an hour. Several of the passengers were sick. The wind continued about the same. The next day was Sunday, and a shark was seen following our ship. An old sailor whose turn it was to be at the helm that day looked back and saw the shark, and he said, “Look out, boys. Some of us will go overboard before 24 hours, sure enough.” Before the sun set, a man named Richard Frome died and was buried. The next morning at four o’clock. Another man, Andrew Loots, died.

April 13: Very high winds and rough seas. So much so that the captain said at noon when he was taking the sun’s altitude that it was the heaviest sea that he ever had seen. The next day, the wind and sea ran down, and it was almost a calm. We caught an albatross, a very large bird. It measured twelve feet from tip to tip. They have very large feet but cannot walk. They live principally on the sea and subsist upon small fish and the crumbs from ships. Again the shark appears after our ship. The next day two men died, one by the name of Jessie Morgan of Staten Island and a man named Pickett from the state of Maine. The next day, it was quite calm all day. There were several sick, but none considered dangerous. We were in better heart and hoped that we would not have to bury any more of our fellow passengers in the sea. We were is latitude 30°20’ south. The next day we had fair winds. We headed south by west in latitude 34°40’. We came opposite the Lapatta river, where sailors have to look out for squalls and hard storms. This place is about two hundred miles wide and a very stiff current.

We were fortunate in getting through it without encountering any storms. The next day, it rained all day and night so that we had to stay below, and we suffered for want of ventilation.

Monday, April 16: The rain ceased, and it cleared off again, and we had fine winds and running 13 knots an hour.

April 17: Running at same rate per mile, or knot. We are now in latitude 40°25’, longitude 31°11’.

April 21: This morning it is very pleasant. The sailors are engaged in lashing all the casks and barrels to the deck. At 4 p.m. a severe gale came up and blew very hard all night. We were in latitude 43°14’, longitude 32°2’. The next morning, the wind was still blowing very hard, Two of the sailors were at work on the bow of the ship adjusting some ropes when a heavy sea struck the ship that came over the deck and swept one of the sailors off that was working on the bow. Instantly, the cry was, “A man overboard!” A passenger who had great presence of mind sprang to the larboard side of the ship and threw a rope over the side of the ship, and the struggling sailor caught it and was hoisted on board. The water was extremely cold, and the poor fellow was almost frozen.

April 22: We encountered a hard storm that lasted 12 hours. We had to close reef the [topgallant sail] and topsails and ran so all day. We had a lottery on board gotten up by the passengers. The prize was a gold watch. Charles Hope was the lucky man.

April 23: The storm has abated, and we had good sailing, but it is so very cold that we could not stay on deck. Last night a man named Moore had seventy-five dollars stolen out of his carpet bag, which caused quite an excitement, for we thought we had no thieves on board, and one would have thought that this would have been the last place to commit a theft in mid-ocean, when there was no possible chance for escape. All were wondering who the thief could be, but they did not wonder long, for the next morning a man named John North came out with a subscription to make up the amount of the money stolen, and suspicion fell upon him at once that he was the thief, and he soon had to stem the tide, for everybody was pointing at him, and he took another man below and handed him the money to give back to the man begging for money. Say that this was his first offense and should be the last, but he was put into irons and sentenced to leave the ship when we should land at Valparaiso, Chile. At five o’clock on that day, a man named Mathew Stout died and was buried in a few minutes after death. That night was very dark And cold, and the snow fell 2 inches deep upon the deck of the ship. We are now in latitude 51°20’.

The next morning, it was calm, which is a very uncommon thing in this latitude at this time of year. Old Prince said, “Look out. We always have a storm after a calm in this region.” At twelve o’clock a gentle breeze set in from the northwest, and we were running 4 knots an hour. Another ship came in sight but not close enough to speak.

Sunday it stormed all day so that we had to stay below. The wind blew so hard that it took four men at the helm with rope and tackle to manage the ship to keep it from foundering. The ship ran quartering toward the land and made leeway very fast. So the next morning, we had to tack ship and run west by south. The next day, we had fair winds again. Two men died—Francis Allen and William Bathgate—and buried the same hour. Died of yellow fever. Took sick on Tuesday and died the following Friday. They were taken with diarrhea and pain in the head, soon becoming deranged and remaining so until death relived them.

A man named Place with two daughters from Ann Arbor, Michigan, were among our passengers. One of the daughters made an ugly charge against her father, and the old man was put in irons., but he did not stay in irons long. Promising to do better, he was released.

The next morning, we came in sight of land. This cry of “Land, ho!” caused great excitement on board, some contending it was land and others that it was not. Some cursing the officers of the ship for running so close to it, while others were rejoicing at the sight of land. The land we had sighted was a small island off the south end of Cape Horn. The next day we had fine sailing, and the captain said to us that we could eat supper off the Pacific Ocean. Supper came, and we were not on the Pacific, and we had sauerkraut and gingerbread for supper, of which we partook with a relish, as we had appetites for anything eatable. The wind continued from the same direction, and the land, heading northwest. We had beans and soft tack for supper but not on the Pacific yet.

THE PACIFIC OCEAN

May 5:This morning we ate breakfast on the Pacific, doubling the cape in the night. The weather was very cold and rough, and the snow fell 4 inches deep on the deck. The next morning a Mrs. Harper from New York, an elderly lady, died at 10 o’clock. She was a very weakly woman when she [died], and she lived far beyond our expectations. She was a widow and had a son in California, also a son and two daughters on board. We saw a number of whales that day, some of the quite close to us. The next day at 2 o’clock, we attended the funeral of Mrs. Harper. The service was read, a hymn sung, and the body was consigned to its watery grave.

The next day the wind blew powerful hard. We came in sight of the western coast of Patagonia and was drifting right toward it. Had it been in the night, we should have run ashore or on the rocks, for the coast along there is very rough and rocky. But we discovered it in tie to tack ship an get away.

May 11: Tremendous storm last night. Sea so rough, and the ship rocked so badly that we had to hold on to our bunks all night to keep from rolling out. Under such circumstances you can easily guess how much we slept. We ran under close-reefed topsails and mizzensails all night. The next night at 8 o’clock Miss Sarah Place died, a daughter of the old man spoken of a being in irons. The next morning we assembled in the cabin to attend the funeral of the deceased lady.

May 12: It rained all day and was very dark and foggy. We headed due north with very light winds. In rainy weather at sea, the sea is always smooth. Let the sea be ever so rough and then comes a hard rain, the sea will become calm in a very short time.

May 13: The rain continued to fall without ceasing all that day. A man named Alex Black died at 8 o’clock that night and was buried the same hour without any service. This man was from Connersville, Ohio. He was a very nice young man, always cheerful and jolly, going to seek his fortune before marrying the girl he left behind, as one of her comrades told me the sad story of his betrothed and the young lady’s parents objecting on account of his poverty. The death of this young man was mourned by all on board. A death or funeral at sea is always sad, but this was the saddest of all to me.

Before leaving New York, I wished for my wife and family to accompany me, but after I had been out to sea two weeks, I rejoiced that they were not with me. When I saw the wife of Mr. Beesley, a young woman who only a few hours before her death seemed the very picture of health and bid fair for as long life as any of us, buried in the deep blue waters of the great ocean. This was our first death and burial at sea and made us all no doubt all of us thought, “Shall this be my fate” Shall I be buried in the sea?” For we all knew that God was no respecter of persons. That when his call comes, we must obey. Sad, sad is a burial at sea.

May 14: The sun came out and the captain was able to take the sun’s altitude—the first for several days. This is the only certain means of telling just what latitude and longitude [you] are in. Al other means is uncertain half guesswork.

CHILE

May 15th. Fair winds and pleasant weather. Sailing 10 knots an hour. We headed east by north, and at 4 o’clock we came in sight of the coast of Chile, but it was a great distance off. Now in latitude 40°00’, longitude 64°03’.

May 16: We had head winds all day so we could not make any headway. We tacked ship several times during the day and thereby held our own.

May 17: Still having headwinds, and we continued to tack ship. At daylight this morning a ship was in sight and seemed to be heading toward us. The wind being fair for her, she soon came up in plain sight. Two men could be seen in her foretop mast and two in her maintop mast, which told us plainly that she was a whale ship, and the men in the masts were watching for whale. They soon came up within speaking distance. They inquired where we were from, how long we had been out, and whether we had any sick on board. Our captain answered from New York, 96 days out, and all well.

Our captain asked the whaler where he was from, how long out, etc., and the answer was from Newfoundland, 165 days out, and had got 220 barrels of oil and that all was well. We were soon out of sight of the whaler, and soon after leaving her, we saw several whales.

May 18: It rained all day. We were afraid of running ashore, for they could not take the sun’s altitude and could not tell just where we were. So we had to run west to make sure of not running on shore. We saw great schools of whale that afternoon.

May 19: More head winds, and we had to run first east and then west to keep from running back. We are in latitude 36°10’.

May 20: Still having head winds. We began to get very much discouraged, for we were within one day’s sailing from the port of Valparaiso, Chile, if we could only get a fair wind to carry us in that direction. We saw more whales and the largest school of porpoises that I saw during the voyage. They came from every direction. The sea was black with them.

May 21: Wind continued the same and about 9 o’clock that night when all of a sudden in the twinkling of an eye the wind changed and sent our ship astern, and we came very near sinking. This is the most dangerous thing that can happen to a ship at sea.

May 22: Bad storm all day. Between 10 and 11 o’clock that night, something appeared on the ends of the foretopmast guard arms that looked exactly like balls of fire. The sailors called it [compizan] and said it was a sure sign of hard storms. In a few minutes, we saw a large waterspout coming right toward us. We immediately changed our course, and it passed by us but quite close to us. It was a beautiful sight. The worst roaring noise that could possibly be imagined. Some of our passengers were almost frightened to death, while others slept. As for myself, I could not sleep when there was a storm or a prospect of one. I always wanted to see what was going on, and I watched the sailors, and as long as they did not seem scared, I felt all right. The sailors are all believers in witches, ghosts, and hobgoblins.

May 23: We came in sight of the harbor, but on account of head winds had to lay out until the next morning.

May 24: The wind shifted, and we ran in to port at 8 o’clock. Our anchor was dropped, and the captain of the port came on board, examined the shipping papers, and enquired as to the health of the passengers, crew, and how long we had been out. We had been out 94 days from New York and had lost 13 passengers, 10 men and three women, 12 of which had died since we left Rio de Janeiro. Eleven died of yellow fever, and one of consumption. There being but one sick on board, and he is getting better, we were given permission to land. As soon as the captain of the port left, the natives in small boats began to gather around our ship to carry us on shore for pay. All the English they could speak was “go shore.” Some of them had baskets of apples and grapes, some pears to sell. The fruit was very fine. All of it grew on the island of [Juan Fernando], where Robinson Crusoe, his man Friday, and the goat had such a nice time. The island is only 60 miles from Valparaiso, and a steamer goes over every day, and one leaves the island every day.

Our ship was soon vacated, for all were anxious to set foot on land once more. I was a little late going ashore, and when I landed, I saw about 20 of our passengers mounted on horses and riding through a whooping and hollering as if trying to frighten the inhabitants of the city. The horses here are not so large as our American horse, but they are very fine and handsome, fine travelers, very great runners. They have their manes all close shaved off and are trained to stop at the least check of the rein, as the riders then all ride with a slack rein. They have very poor saddles. It is nothing but a pad, with stirrup leathers and a large wooden stirrup. Their wagons are all carts and gigs gotten up for one horse only. Their harness is composed of collar and harness and rawhide traces. Bridle bit with a strap tied on the end for a whip. They use no lines. Their mode of driving is for one man, the driver, to ride the horse, not the horse hitched to the gig. That horse he leads by the side of the one he is on. The driver wears a big pair of spurs and spurs the one he rides and applies the whip to the other. These vehicles are only made to carry two persons, and you generally see a gentleman and lady riding in them together.

The driving is all confined to the city, for there are no roads leading into the city. Nothing but paths made by pack mules, as everything is brought in over the mountains by trains of pack mules. They even pack all the wood and coal. They have great copper mines not far from the city, and we saw a mule train come in loaded with copper ore in company with three others of the party. I took a tramp out toward the mount, saw several flocks of sheep and lots of mules and horses grazing. It was very short nipping for the poor creatures. For as far as I could see, the sides of these mountains were almost barren. After we had strolled as long as we wanted to, we started back, but not in the same road we had gone out. We soon came to a shanty built of mud, where some persons were engaged skinning a carcass of some kind. When within a few yards of this hut, out came 5 or 6 dogs and came right at us with great ferociousness, but we kept right on and paid no attention to them and came out all right. It was all the way downhill returning to the city, and my knees gave out, and I was very tired and perfectly satisfied with strolling in the mountains of Chile.

We went to a hotel and called for dinner. I was very hungry as well as tired. After dinner in company with about 20 of our passengers, we took in the sights of the city until evening and then returned to the ship. When we returned to the ship, we found our steward drunk and wanting to fight everybody. Finally he found one as willing as him, and they went at in fine style, and when the fight ended, the steward was not near so handsome as he was before the fight. I went to my quarters and wrote a letter to my wife and the next morning went ashore to place it in the hands of the American consul to be sent on the first vessel leaving that port for New York. I had to pay 56 cents postage on that letter.

That day the wind blew so hard from off the sea and the waves ran so high that we could not get back to our ship and had to stay in the city all night. We went to a hotel, called for supper and lodgings. After supper we sat in the office and chatted with the landlord, who spoke tolerable fair English. About 10 o’clock, we called for our beds and were piloted up a rickety pair of stairs to a room that looked more like a hay mow than a sleeping room. Instead of bedsteads, we had stalls. Instead of feather beds, we had shavings. Our quilts and sheets were all blankets, and instead of sleeping, we had to fight fleas and rats all night.

The next building to our hotel was a resort for sailors—a terrible hard place and a lot of drunken Devils kept up a howl at night over the door of that place. The next morning I read the following sign:

Come, Brother Sailor,

As you pass

Lend a hand

To steep this mast

This a bad place for earthquakes. In these mountains are continuous burning volcanoes, which break out very often, causing the earth to tremble and quake so that it shakes down their adobe houses. They do not build any other kind of houses, and they are never more than two stories high on account of the oft recurrence of the earthquakes.

The city of Valparaiso sank in 1836. A man who was there told me all about it. He said in the morning about sunup, the earth began to quake. Some of the houses began to fall, others cracking on all sides, ready to fall any minute. It was not long before another shock still harder than the first and the cry of men, women, and children could be heard in every direction. This shock left but few houses standing, and the falling caused hundreds of deaths. There were a number of shocks during the day. In the afternoon, the earth began to crack open, and water coming up made it evident that the city was sinking. And the inhabitants fled to the hills only a short distance off. In the morning of the next day, the city was out of sight. It had sunk into the sea, and it is probable that our ship was anchored over the spot where the city once stood.

This man related circumstance that happened. There was a young man of his acquaintance at the time who had a beautiful head of black hair on the morning of the earthquake, and at 5 o’clock that same evening, his hair was white as snow from fright. I cannot vouch for this, but I believe the man told the truth.

The next day I visited some of the fine gardens in the city. These are mostly kept up by the French and English inhabitants of that city. They are very fine. All the enterprising people here are foreigners. The natives of this country are a very indolent and slothful race of people as a rule. Ten Americans can command double and triple the wages here that of a native. They tried hard to hire some of our men—blacksmiths and carpenters—offering them five and six dollars per day but could not persuade any of them to stop off.

I next visited the cemetery, and this is the manner in which they bury their dead. The common herd of poor class they bury all in one common grave. They dig a hole 40 or 50 foot long and 10 or 12 foot deep, and when one dies, they throw the body in without any coffin and throw just enough dirt on to cover it up. And when another dies, they throw it on top of that and a little more dirt, and so on until that hole is full and then dig another. I saw the legs and arms of several sticking out. In this way hundreds are buried in one common grave while the wealthy class and all foreigners are buried in single graves in coffins.

There are a great many sailors buried here. I noted some of the inscriptions or epitaphs on some of the tombstones:

To me remains no place nor time.

My country is in every clime.

I can be calm and free from care

On any shore since God is there.

After many toils and perils past,

In foreign climes I fell at last.

Reader, prepare to follow me,

For what I am you soon must be.

Ship mates, all my cruise is up.

My body moored at rest.

My soul is where? Aloft, of course,

Rejoicing with the blest.

I found this epitaph on the tomb of an old sea captain, buried here in 1828:

Here lies the rigging spars and hull

Of sailing master David Mull

The following lines I found on the tomb of an America lady buried here:

Light be the turf of thy tomb

May its verdure like emerald be.

There should not be the shadow of gloom

In aught that reminds us of thee.

These lines were inscribed on the tomb of an American Sailor buried in 1840:

With bounding heart I left my home

Not thinking death so near.

But here the tyrant laid me low,

Which caused a messmate’s tear.

I might have taken many more of the inscriptions, but the day being almost gone, I had to stop and retrace my steps toward the city in order to reach there before dark, as I had some suspicion of these natives, especially in the dark. They all carry their big, dark knives by their side, attached to a belt, and they both fear and hate a Yankee.

Sundays here is their day for sport, horse racing, bull fighting, and all sorts of gambling. A great race was to take place on Sunday while we were there. And as we wanted to see all the sights, we went out to the race course. Thousands of people were there. The races were very fine—very fast running horses and piles of money bet on them. After the races were over, two of the men that owned the horses commenced quarreling. They were both mounted on horses, and very soon they drew their revolvers and made a dash at each other. And when the smoke cleared away, both of these men lay dead upon the ground.

For sin and licentiousness Valparaiso excels any city in the world of its size. Even the women are so depraved that they have no shame.

There was an English Man of War anchored close to our ship while we lay in this port, and on Sunday they sent an invitation to our ship to attend church service on their ship at 4 o’clock p.m. Eight of us in a small boat rowed over to their ship, and we were a little too soon for church. They took great pleasure in showing and explaining everything on their ship. Also their implements of war. They had 36 cannon and large amounts of muskets with glittering bayonets. Everything was very clear and neat and in proper place, much more so than on our ship. It was not long until the bell rang for church, and all hands gathered between decks and were soon seated on benches. The chaplain read the services and prayers, and every word was repeated after him by all the soldiers, sailors, and seamen. Soon the bell tolled again, and the services were ended. The benches were all stowed away, and the brooms were brought out and sweeping commenced. They do not allow a speck of dirt to accumulate in any part of the ship. They invited us to remain to supper with them, and out of curiosity to see how the lived, we accepted their invitation. I did not eat much, for all they had was pilot bread and tea, and the bread was so hard that I could not eat it. They had 260 soldiers on board. Then we left them, they shook hands with us and wished us good luck.

May 31: All ready to sail, and when our captain went to the consul to get his clearance papers, he found that someone had filed a petition against allowing the ship to go without being thoroughly cleansed and whitewashed. So he could not get his clearance. We had three doctors on board, and they went to the consul’s office and prevailed on him to issue the clearance, promising that they would have the ship cleaned as soon as she got to sea. The wind blew from off the sea so hard all day that we could not run out.

BACK TO SEA

June 2: At 4 o’clock p.m., the wind and tide both being favorable, we weighed anchor, set sail, and were soon out of sight of the city. The next morning, the [Burning] Andes mountains were still in sight, but by 4 o’clock, we were out of sight of them.

June 4: We had fair winds, running 10 knots an hour, heading northwest. Quite a number of the passengers were seasick again, and several of them with bad diarrhea., two of which were considered dangerously ill. There were William Adams and Joseph Gregg. That night, we had a hard storm, but nothing serious happened. We were then in latitude 31°45’, longitude 14°15’.

June 5: We had continuing winds all day so that we could not make any headway. The sun did not come out, so the observations could not be taken.

June 6: Fair weather and light breeze from the southeast. We headed southwest and ran 4 knots an hour.

June 7: Fine weather, and we had the best day’s sailing we had since crossing the equator—a 12 knot breeze all day and heading straight on our course. Which made us feel good. Our manner of living was also changed, which was also encouraging to us. As we had previous to running into Valparaiso, lived very poor. About all we had to eat was hard bread and salt beef and tea, and sometime not enough of hat, but now we have potatoes and onions. This morning, we had a fight between decks. Two men in mess No. 11 fought over the matter of the knives not being scoured.

June 8: We had fine weather and fair winds. The carpenter, who is always called Chips at sea, and all the sailors are engaged putting up [rogel masts] on the foremasts, mainmasts, ad mizzenmasts so that we can put on three sails more than we have ever had up, and when they were up, we sailed at a rapid rate, often making 15 and 16 knots an hour. Our sick are all getting better again, which makes all of us feel much better, for we dread to see our fellow mortals buried in the sea. And when this happens, everyone on board cannot help but think who will go next. The very thought of sight of a burial at sea is anything but pleasant to anyone.

June 9: Cloudy weather and light winds but fair to take us on our course, which was northwest. I thought as the ship was running so steady and the sea was so smooth that I would join the army of washers that were on the upper deck and wash a couple of shirts for myself, and at it I went. This made me think of home more than ever, as I never before undertook to wash clothing. I used to think when at home and see women washing and singing that it was a light job to wash, but now after this trial at washing with salt seawater, with soap having no effect on dirty garments, it was rather amusing at all events. Gentlemen from all over the States cam marching out on deck with their dirty garments and laughing and [guying] each other. Some would say, “oh, Lord. Did I ever think that I should come to this.” Some would say, “If I were at home, I have a good wife, a mother, or a sister to do this kind of work.” This is the fate of all persons going to sea on a long voyage. They must expect all manner of trials and hardships.

If it is a man of a family and of any feeling, he is forced to reflect on his home and friends, a wife and children, or perhaps a father and mother, sister or brother, whose minds are perhaps troubled on account of him who is at sea. If it be the wife, this will undoubtedly be her song:

Come sing a song of absent friends

Who left us all alone

I feel so sad I scarce can smile

For husband dear is gone.

I miss him when from my sweet sleep

I rise at morning light

And, oh, I wish him back again

When mother says good night.

I miss him at the social board

I miss him at my play

Who is so serious when we are sad

Or lively when we are gay.

Oh, haste, good ship and bring him back

Across the ocean’s wave.

I’ll pray to heaven every night

My husband dear to save.

June 10: We had fine sailing. The day was clear and bright sun shone. We headed northwest by west and ran 9 knots and hour.

June 11: The wind still continues from the same direction. This is the eighth day that we had the wind from the same quarter. It did not vary one point in the five days our course was northwest. In latitude 19°24’.

June 13: Sunday. The weather is very fine, and the same good old breeze sending our ship on its course. We spent the day reading the Bible and other useful books and singing songs. We had lots of good singers on board, and we made the fishes of the sea come up to the surface to see what the noise meant. Sometimes a hundred and fifty or two hundred would join in some chorus.

There was a man on board with two little children that were very interesting—a girl and a boy. The little boy’s name was Jack. I thought of my own little boy I had left at home. I would take him up often and imagine it was Charley. He had light hair and looked like my boy.

June 14: We struck the southeast Trade Winds and had fine sailing, running 9 knots an hour in latitude 14°55’.

June 15: Winds continued the same and running at same rate in latitude 12°18’, longitude 92°15’.

June 16: Wind not quite so strong, but we ran 8 knots an hour. We had a lottery on that day. The prizes were gold watches. Now in latitude 10°9’, longitude 95°8’.

June 17: We were sailing on with same Trade Winds, still heading northwest with wind right aft, running 10 knots and hour. The ship ran so steady that not a rope was changed during the day or night. The thermometer stood at 95° in latitude 8°15’, longitude 96°14’.

June 18: The day was clear, and the sun was hot. Had it not been for the good breeze that still kept up, we should have suffered, for we had no awning up to keep the sun off of us. We saw a finback whale off our lee bow only a short distance from us. This was a different kind of the whale family from what we had seen before. Thermometer 80° in latitude 6°36’, longitude 98°17’.

June 19: Our good wind still continued and increased in volume, and if there ever was a merry set of men, we of the ship Race Hound were among the merriest of all: after having rocked and tossed around Cape Horn, we began to think of the poem Whatever Is Is for the Best:

Wherefore repine at fortune’s frowns

Sorrow must be thy frequent guest

In every trial think of this:

Whatever is is for the best.

Despair not though thou seldom finds

From care a momentary rest

Press on in faith and fullest hope

Remembering all is for the best.

When sad misfortunes weigh you down

And dark forebodings haunt the breast

Be this thy beacon light through all

Whatever is is for the best.

Then trust in God if you would find

Beyond the great eternal rest

For orders he not all aright

Whatever is is for the best.

These lines were corresponded by my bunkmate Richard Bliss from Flint, Michigan, a capital good fellow and such a man as I love to meet on such a voyage as this. He was always cheerful and happy. Late this afternoon we had several squalls and light shower s of rain, but nothing serious happened.

June 20: Sunday came, and the sun shone brightly—not a cloud in the heavens and a most glorious breeze from the west, which was cool. And it was so pleasant that all seemed to rejoice. The awning was spread to keep the sun off or else we should have suffered with heat. But with this and the cool wind that carried so rapidly along, we were quite comfortable. We spent the day in a variety of ways: some reading, some writing, some singing. As for myself, I spent the day reading the Bible, pacing to and from on the deck. My thoughts were constantly on home and the privileges they were enjoying in going to church or of visiting friends that beautiful day, while I was confined to the decks of a ship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. This seemed the most like a Sabbath day of any day since the beginning of our voyage. The sailors were all still, and the passengers—those of them given to profanity—had in a great measure reformed since the death of so many of their fellow travelers who had fallen victim of a watery grave.

The thermometer stood at 90° in latitude 2°3’.

June 21: Our winds were very light, the sky bright and clean. At 12 o’clock noon, we were within 29 miles of the equator and at the rate we are funning we will cross the line about 9 o’clock tonight. We saw a sperm whale close to our ship—the largest we had seen.

June 22: On this day the sun reaches its northern extremity and is 22 ½ degrees north of the equator and is the longest day in the year. It is called the ecliptic of the sun. About 10 o’clock our breeze set in a little stronger, and we began to make better speed. And at 12 o’clock we were 20 miles north of the equator.

June 23: Breeze from the south very light but so steady that it took us on our course. The day was clear and very hot. I went up on masthead and sat and read all day. In the evening the sailors gathered on poop deck and had a dance, and they all got drunk, and they carried on all night so that we got no sleep for their noise. The mate being sick was all of our dependence. This captain was afraid of those wicked wretches, and they were wanting a chance to kill him as they had a grudge against him for some of his cruel treatment of them. Some time before when they were all sober—and if they had have tackled him, there would not have been much mercy shown him from the passengers, for he had treated us all badly by not giving us enough to eat or to drink. We were promised when we left New York that we should all fare alike in first and second cabin—that our provision should be the same. But before we were out a week, there was a material difference in the grub, which kept up a row all the time. Before we were out 20 days, we were passed our allowance of water, which was only one quart for each man a day; however, as small as this quantity appears, I never suffered for water at any time during the voyage. As we did not have much exercise, but little water was required. But worst of all, the water got so bad before we could reach a port to get fresh water again. The water smelled so bad that we would do without just as long as we could, for the smell was enough to set one to vomiting. We kept haunting the captain until we got fresh bread baked every morning instead of hard tack, which was so hard that no man could eat it without grinding first.

June 24: This morning had every appearance of a good day for us. The wind was strong and fair, and we were making fine headway when all of a sudden about 10 o’clock black clouds came up from the northeast and soon overshadowed us. And in a few minutes, the rain fell in torrents for about 2 hours, when it ceased and a favorable breeze struck up again. Before this, I had been sleeping on a deck for about a week. But when this rain came, we all had to go below, where we suffered for want of air. But the showers being short, we were soon on deck again. It was too cloudy to get the sun’s altitude. We could not tell what latitude or longitude we were in.

June 25: The morning appeared very pleasant, but we had several showers of rain during the day. All being well, we were all merry, and some of them got a little too merry. Six or eight of our men got on a spree and showed off a little. They made so much noise that the captain came on deck and ordered them to go forward, but they drove the captain to his quarters in a quick time. And when they had as much fun as they wanted, they got quiet and went to bed.

That night we came in sight of the North Star—which was the first time we had seen it since leaving north latitude on the Atlantic 87 days before! When I saw it, I resolved that I would never go out of sight of it again. The sun and moon began to rise and set in their proper places again, and things began to appear natural again. We had never been used to looking north for the sun before. Neither had we used to having two summers and two winters in the same year. But we have seen them this year. We have felt the burning heat of the sun a second time at the equator and felt the sleet and snow a second time. Leaving New York in the winter, we encountered another winter on rounding the cape, and a severe winter more so than on land on account of the velocity of the wind. A voyage on the high sea is the place to try the courage of men and to learn their disposition. Some men during storms would go below and crawl into bed and cover up head and heels to keep from witnessing the awfulness of a storm at sea. Some would pray with all their might. Some would not leave the deck while the storm lasted. For my part, I was always among the latter and could never sleep during a storm no matter how long it lasted. I always watched the old hands. As long as I could not see that they were alarmed, I felt that we would come out all right.

Now we have been 20 days without the least appearance of a storm or a calm, which is very pleasant after coming around the cape through so many storms and gales of wind and the dangers of going ashore or on some hidden rock or island—all of which the sea is full of around the end of the cape. We are now in latitude 5°40’, longitude 100°11’ west, thermometer 85°.

June 26th. We had a ten knot breeze last night and this morning until 4 o’clock, when it began to rain. The wind full, and it is almost calm until 12 o’clock, when a light breeze set in from the northwest. We were then in latitude 7°18’, longitude 111° west.

June 27: Sunday morning I was up early and went forward under poop deck to take a saltwater bath, as the water was warm and the day was pleasant after a hard rain last night. The air was very pure now, this being the sabbath and almost a calm. Everything seemed to quiet, and almost everyone had a book in their hand—even the sailors, who on every Sabbath before that but one could be heard cursing and swearing. Cursing their God and the contrary winds often to such an extent that it was enough to chill the blood of anyone possessing a soul to hear them. We saw a shark that day, but it was some distance off and going the opposite direction. We were glad of it for none of us wanted to supply his hungry belly.

June 28: This morning just as I went on deck, two men on top of the [gella] got into a fight, and it was about the worst fist fight I looked at. They were both big, strong men, and they fought for 5 minutes or more. Both badly pounded and was blood all over.

June 29: We are having strong winds and showers of rain and sudden gales and squalls. Continued all day. It was so cloudy and stormy that the captain could not take the second altitude to determine what latitude we were in.

Last night there were several large birds gathered around the ship. These birds were about the size of a goose and of a brown color. The sailors called them boobies. They are sleepy, lazy kind of bird, and they fall asleep as soon as they light. They had scarcely settled down when the sailors had hold of them and brought them on deck. But they did not hurt them and let them go again. They consider it bad luck to kill a bird of any kind on the sea. There were other birds around the ship called the men of war. They are a white bird and about the same size of the booby, they did not light. There are but two sea fowls that ever light on a ship—the booby and the albatross. The latter is a white bird with black spots on their wings, web footed, and the largest bird of all.

June 30: We had a very bad storm last night. I thought one time we were going to go down. Several of the passengers rolled out of their berths. But fortunately the storm did not last but a couple of hours. Hard rain began to pour down, and that had a tendency to still the troubled waters. I attempted to sleep on a bench near the hatchway, but it was so awful hot that I could not sleep. Besides, I had not laid there but a short time until the bench capsized and I was laying on the floor. I pecked myself up and went up on deck and spent the night there, where I could get a good breath. When daylight came, the wind shifted to the northwest, and we made a rapid run. It rained very often all that day.

While we were at breakfast this morning, someone on deck cried, “Sail, ho.” When we came up on deck, we saw the masts of a vessel supposed to be about 6 miles off our bow, heading the same way we were. But she was running double reef topsails and mainsails with [topgallant] sails furled. Making very slow time. We were running under [studding] sails with our [topgallant] sails and [royal] sails all set. It was not more than 2 hours from the time we first sighted her until we were out of sight.

FROM SEA TO LAND

July 1: This morning after a refreshing sleep on deck, we found our ship sailing very fast, and the sailors said we had been running at that rate all night. About 8 o’clock it commenced to rain and rained for 3 hours very hard. Then it cleared up and the sun came out, so the captain got to take the sun’s altitude. And we found we had been making very fast time for 3 days—the fastest we had ever made. We had run 924 miles in 3 days and night. We are now in latitude 18°47’.

July 2: I slept on deck again, and it was uncomfortable cool. We passed a ship at 1 o’clock this morning and at daylight were almost out of sight of her. She was going the same way we were. They day was cloudy and very cool. This is very strange in this latitude, as we were almost directly under the sun. On account of clouds, we did not get the sun’s altitude that day. We saw a large shark pass under the bow of our ship that day and went right off from us. It had been a long time since we had seen one. We were then in the northeast Trade Winds, and a shark is very seldom seen here. We were glad to part with him. The Trade Winds are very strong and steady, and we are sailing very rapidly.

July 3: The weather continues very cool, and the wind strong and fair. We wet on deck at 4 o’clock to arrange for the celebration of the 4th of July. We appointed a committee of three to select a speaker from among our passengers and to make such other arrangements as was thought proper for the occasion, and the committee after due deliberation decided that as the 4th came on Sunday, we should celebrate on Monday, the 5th.

July 4: Strong headwinds and very cold for this latitude. It was so cool that we had to go below to sleep. This was very discouraging to us. We had only about 15 degrees to run on a straight line and could make that in 4 days if the wind was from the right direction. We wanted to run north but had to run west, which was carrying us farther off every hour. The steward killed a hog, which was the last hog with 4 legs we had on board. We had duff for dinner today. Duff is a boiled pudding and is served once a week onboard of the ship. Today we are in latitude 24°18’ north.

July 5: We are heading northwest by west with strong wind and cool weather. At 11 o’clock we assembled on quarterdeck where the chairman, Mr. Shulery called the meeting to order and introduced Mr. Puleifer as the orator of the day. He immediately came forward and commenced his address. He spoke for about an hour. His speech was well prepared. The sailors hoisted a flag on the forward deck with a large dog on it, with these words written on it: Splice the Main Brace. The captain, seeing it, ordered the mate to go and take it down. He obeyed the command, and soon their flag lay upon the deck. After the speaker was through, Mr. Bliss, Mr. Shaw, Mr. Warner, Mr. Eliott, and Mr. Topliff all offered appropriate toasts, and volunteer responses were made. The “Star Spangled Banner” was sung, and the crowd dispersed. The stevedores all got drunk and some of the sailors. The officers of the ship kept sober, or we might have had a serious time. This was the coldest 4th or 5th of July I had ever seen, and we were only 2 degrees from under the sun. We are in latitude 26°21’.

July 6: Our course is northwest, and we are running 10 knots an hour. Nothing special happened during the day. Now in latitude 28°11’.

July 7: Wind and weather the same. Running 20 knots an hour in latitude 30°14’.

July 8: We began to get very much discouraged, as the wind was still at our head. The way we are running, it would take us [missing words] to run up to San Francisco, when if we could have fair winds, we could run in 3 days. As is, we are running farther off every minute and no hope of a change that we could see. The weather still very cool in latitude 32°9’.

July 12: This morning it rained a light shower and then cleared off and was calm all day. This was the first day the sun had shown all day since we crossed the equator, and it was warm enough to be comfortable. We were now in latitude 38°40’, exactly opposite San Francisco but about 800 miles off and in a dead calm, which is not very encouraging.

July 13: We came out this morning after a refreshing sleep and found we were still in a calm. The sea looked very beautiful; not a ripple could be seen in any direction. Two seabirds were the only objects in sight. At about two o’clock in the afternoon a light breeze set in from the northwest, which was a favorable wind of us, as we wanted to run east immediately. The yardarms were squared, and the [studingsails] were set, and we began to more again toward the promised land.

July 14: We had a splendid wind all day that carried us at about 10 knots per hour right on our course, which was east by north. You may guess how good we felt when we got out of a calm. All were in fine glee, thinking we should get to set foot on terra firma once more. The land of promise, which we had for so long a time had been so anxious to see

July 15: Wind still continues fair for us, and we are making good headway. The passengers are beginning to gather up their belongings and making preparation for landing. All are engaged in washing and drying their clothing and blankets, so as to have all clean to go on shore. When the captain took the sun’s altitude, he said we were just 11 degrees from San Francisco.

July 16: Our breeze was light but right to the purpose. At 10 o’clock today we are 27 miles from the city. The baker and the cabin boy had a fight.

July 17: This morning we have a splendid breeze from the southwest. While at breakfast this morning, someone cried, “Whale!” We went on deck and saw a large tree with limbs and roots all floating on the water. It was supposed to have come down the Sacramento River. All cried, “Land!” on our weather bow, but it proved to be a cloud. And the day passed without seeing land. Very cloudy and cool.

July 18: This morning when we got up, we were right close to the land. Just as the sun came up, a pilot came on board to pilot us into port. We passed through the Golden Gate at 11 o’clock and dropped anchor. We had to pay one dollar to be taken on shore, as they would not allow our ship’s boats to land our passengers. One of them attempted to go but had to come back. The rules of the port had to be complied with. We landed at the Pacific Warf and took dinner at the Howard House, for which we paid fifty cents.

At 4 o’clock we went on board the river steamer Brighton for Sacramento and landed the next morning at 8 o’clock. Here we stopped at the Globe Hotel and remained there until the next day. Here we took the stage for Marysville and landed there at 4 o’clock in the afternoon and stopped at the Eagle Hotel. Our bills were 50 cents per meal and nothing for the lodging.

The next morning we took the stage again for Dobbins Ranch, which was 25 miles from Marysville, for which we paid four dollars each. We landed there just as the sun was setting. We had to pay one dollar for a meal.

The next morning we started out on foot, bound for Frenchman’s Bar on the Uba River. The road was very rough and hilly, and we had our blankets and luggage to carry. We came very near giving out. We had been to sea so long and having no exercise that were not in very good trim for traveling on foot. I was more fleshy heavy than I ever was in my life—and consequently short to breath.

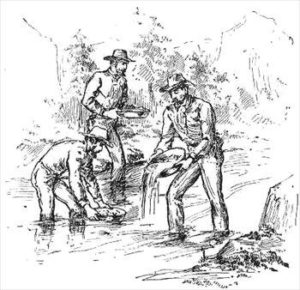

When we got to the ranch, we put up at the house of John Higgins. We inquired of him the prospect for mining, and he made us believe that it was excellent. We asked him the price of boarding, and he told us ten dollars a week in advance. So we paid him ten dollars each for a week’s board, and then bought a pick and shovel, for which we paid five dollars each. Feeling very tired, we did not start out that day.

The next we shouldered our picks and shovels and pans and started out, but after digging several holes and washing the dirt, we could find nothing that looked like gold. The next two days we attended with the same kind of success. After a search of three days in vain, we concluded that this kind of work would not do. We should soon be minus what little money we had left. So we determined to hire by the month, as wages was good. So myself and one of my company went to a steam mill owned by an old Chilean named Lameis, where we had no trouble in getting employment of a hundred dollars a month.

He set my partner to driving oxen teams made up of the wildest kinds of Mexican cattle that did not know gee, haw, nor anything else and had to be lassoed every morning to get the yoke on them. He kept 3 or 4 Mexican men for that purpose. We went to work, but we did not stay long, as they did not give us enough to eat. And what there was the dogs would not eat without the dog was starving. When we went to the table, the boy that waited on the table would come around and lay a dirty looking cake at each pate and say, “One hombre, one bret.” And this was all we could get. At the end of seven days, we could stand it no longer, and we called on the old man for a settlement. He paid us off very promptly, and we left him alone to enjoy his dirty hash.

We then went back to Frenchman’s Bar, where we bought a share in a fluming company that was [searching] the bed of the river, for which we paid two hundred dollars down and agreed to pay four hundred more when they got it out the claim. So we worked on this way for two months. But before we got the water all dammed off, there was not work for us all. So I left them and wet to Dry Creek, distance of 15 miles, for the purpose of taking up some claims then but could find none worth taking. But I stayed there some three weeks and worked by the day at four dollars a day.

While I was there, the news came to me that our river investment was a total failure. We had lost our money and hard work. I set down and studied the matter all over, and finally I came to the conclusion to go to Sierras old diggings about 50 miles up the mountains and at the base of Table Mountain—or more properly Sierra Nevada Mountain on the east side of Slate Creek. On leaving Dry Creek, I left the 2 men, Braddock and Durbin, with whom I had doubled the cape and with whom I had been partners since we landed in California. And I never met them again while in the state.

The country up here in the Sierra Nevada mountains is very rough—so much so that wagons cannot get up here. Everything is brought up here by pack trains. Trains of mules with pack saddles on will come up, 50 or 60 in a train, all loaded with provisions or something that the miners have to use. Each mule will carry from 2 to 3 hundred pounds. A man goes before on a horse with a bell on, and the mules will follow, one right behind the other. Sometimes the train is half a mile long. A Mexican follows behind to see that no mule drops out of the train or loses his load.

These pack trains are all owned and operated by Mexicans. You can hear them when they get within ten miles of us, coming down the mountain on the west side of Slate Creek swearing at the mules in Spanish. Their mule talk is hepo mulo sacare camaho.

There was a cabin close to our cabin that had a parrot, and that parrot would always hear the mule train coming before anybody would know if it, and it would begin to holler hepo mulo. Then in about 6 or 7 hours the train would arrive in camp with its cargo.

I was to relate a circumstance that happened at Frenchman’s Bar while I was there. It happened on Thursday night while I was at church. A man came to the cabin of Mr. Ross. He was a gambler and commenced to gamble, as all of those houses that kept boarders had a gambling table. His cash soon gave out. He had a large buckskin sack that he said was full of gold dust. He showed the sack to Mr. Ross and told him that he did not want to break in on it and asked him to loan him ten dollars, which he did, supposing he would shortly pay him back. The gambler was soon fleeced out of that ten dollars. He got up and set around from a while and then slipped off and came over to the house of Mr. Higgins, where I was boarding, and commenced playing again. He soon lot, and the buckskin sack was again exhibited, and he borrowed money again. This time the lender had the sack opened and found nothing in ti but black sand. And a row was kicked up immediately, and Mr. Ross was informed of the contents of the sack. He came up immediately and took the gambler by the throat and demanded his money. The fellow said he had not a cent of money in the world. They took him out stripped of all clothing but his pants and tied him to a tree and gave him twelve lashes and then gave him one hour to leave.

When they were fixing to whip the gambler, there was a man named Brown in [favor of] having the fellow whipped, and the gambler drew from a scabbard that hung by his side a large butcher knife, intending to stab Brown but Mr. Ross was standing right behind him and caught his arm. In drawing the knife, he struck a small boy in the shoulder, inflicting a sever wound. When they had the gambler tied to the tree and had given him 12 lashes, the little boy said, “Now give him 12 lashed for me,” they they untied the fellow and let him go. And with the blood running down into his boots, he was soon out of sight.

SEARCH FOR GOLD CONTINUES

Now I will return to the Sierra diggings. I came here on the 20th of September, 1852, on Sunday and stayed at the Sierra House at Chandlersville. He charged me one dollar for meals and nothing for lodging. This morning I started out prospecting, but I was sick for the first time since I left home. I layed down by a large red cedar log and layed there all day. Has it [not] been for some medicine my partners had given me, I would have had the [cholera]. The next day I felt some better but not able to work. But the next day I felt strong enough to work, and I went to digging holes in the ground to find gold. I kept this up for 5 days without any success. So I gave up prospecting and went and hired to work for 3 dollars a day to an Englishman. I worked 7 days and then quit. And then in company with 3 other men from [Ceeder Country Soway] by the name of McAfferty, Hardacher, and Moffit, we took a contract digging a ditch 125 feet long, 6 feet wide at the top and 4 feet at the bottom. It took us 26 days to do the work. We got six hundred dollars in cash and the dirt that we threw out of the ditch, which proved to be fairly good paying dirt.

After we completed this job, I jumped a claim that a man had forfeited by not keeping notices on it or working it. I went to work on it, and while I was sinking the first hole, this man came along and ordered me off. But I paid no heed to him. He went away, and I never saw him afterwards. After working this claim for a short time, I found a chance to buy a share in a claim with three other men: a Mr. Henry from Iowa and two men named Watkins from Kentucky. They had four claims of one hundred feet each and a small cabin, for which I paid $85.00. And then we held equal shared in the claims.

We had on hand 80 dollars’ worth of provisions at that time, which was only about enough to last us 2 weeks, as provisions were very high. At that time, $80.00 would not buy much more than one man could carry at one load. Flour was selling for 40 cents per pound, cornmeal at 28 cent, pork 59 cents, sugar 25 cents, molasses for $3.00 per gallon. Boarding by the week at boarding houses $14.00 to $16.00, in advance wages $6.00 per day.