Trip to California, Nimrod Headington’s journal, [1] details his journey by ship, sailing from New York to San Francisco, to pan for gold in 1852. [2]

This is the eighth in a series of blog posts, the transcription of Nimrod Headington’s 1852 journal.

Today’s installment begins on 24 May 1852, and they have just dropped anchor off the coast of Chile, near Valparaiso, and are ready to disembark. They had been at sea nearly 95 days.

[24 May 1852] Our ship was soon vacated, for all were anxious to set foot on land once more. I was a little late going ashore, and when I landed, I saw about 20 of our passengers mounted on horses and riding through a whooping and hollering as if trying to frighten the inhabitants of the city. The horses here are not so large as our American horse, but they are very fine and handsome, fine travelers, very great runners. They have their manes all close shaved off and are trained to stop at the least check of the rein, as the riders then all ride with a slack rein. They have very poor saddles. It is nothing but a pad, with stirrup leathers and a large wooden stirrup. Their wagons are all carts and gigs gotten up for one horse only. Their harness is composed of collar and harness and rawhide traces. Bridle bit with a strap tied on the end for a whip. They use no lines. Their mode of driving is for one man, the driver, to ride the horse, not the horse hitched to the gig. That horse he leads by the side of the one he is on. The driver wears a big pair of spurs and spurs the one he rides and applies the whip to the other. These vehicles are only made to carry two persons, and you generally see a gentleman and lady riding in them together.

The driving is all confined to the city, for there are no roads leading into the city. Nothing but paths made by pack mules, as everything is brought in over the mountains by trains of pack mules. They even pack all the wood and coal. They have great copper mines not far from the city, and we saw a mule train come in loaded with copper ore in company with three others of the party. I took a tramp out toward the mount, saw several flocks of sheep and lots of mules and horses grazing. It was very short nipping for the poor creatures. For as far as I could see, the sides of these mountains were almost barren. After we had strolled as long as we wanted to, we started back, but not in the same road we had gone out. We soon came to a shanty built of mud, where some persons were engaged skinning a carcass of some kind. When within a few yards of this hut, out came 5 or 6 dogs and came right at us with great ferociousness, but we kept right on and paid no attention to them and came out all right. It was all the way downhill returning to the city, and my knees gave out, and I was very tired and perfectly satisfied with strolling in the mountains of Chile.

We went to a hotel and called for dinner. I was very hungry as well as tired. After dinner in company with about 20 of our passengers, we took in the sights of the city until evening and then returned to the ship. When we returned to the ship, we found our steward drunk and wanting to fight everybody. Finally he found one as willing as him, and they went at in fine style, and when the fight ended, the steward was not near so handsome as he was before the fight. I went to my quarters and wrote a letter to my wife and the next morning went ashore to place it in the hands of the American consul to be sent on the first vessel leaving that port for New York. I had to pay 56 cents postage on that letter.

That day the wind blew so hard from off the sea and the waves ran so high that we could not get back to our ship and had to stay in the city all night. We went to a hotel, called for supper and lodgings. After supper we sat in the office and chatted with the landlord, who spoke tolerable fair English. About 10 o’clock, we called for our beds and were piloted up a rickety pair of stairs to a room that looked more like a hay mow than a sleeping room. Instead of bedsteads, we had stalls. Instead of feather beds, we had shavings. Our quilts and sheets were all blankets, and instead of sleeping, we had to fight fleas and rats all night.

The next building to our hotel was a resort for sailors—a terrible hard place and a lot of drunken Devils kept up a howl at night over the door of that place. The next morning I read the following sign:

Come, Brother Sailor,

As you pass

Lend a hand

To steep this mast

This a bad place for earthquakes. In these mountains are continuous burning volcanoes, which break out very often, causing the earth to tremble and quake so that it shakes down their adobe houses. They do not build any other kind of houses, and they are never more than two stories high on account of the oft recurrence of the earthquakes.

The city of Valparaiso sank in 1836. A man who was there told me all about it. He said in the morning about sunup, the earth began to quake. Some of the houses began to fall, others cracking on all sides, ready to fall any minute. It was not long before another shock still harder than the first and the cry of men, women, and children could be heard in every direction. This shock left but few houses standing, and the falling caused hundreds of deaths. There were a number of shocks during the day. In the afternoon, the earth began to crack open, and water coming up made it evident that the city was sinking. And the inhabitants fled to the hills only a short distance off. In the morning of the next day, the city was out of sight. It had sunk into the sea, and it is probable that our ship was anchored over the spot where the city once stood.

This man related circumstance that happened. There was a young man of his acquaintance at the time who had a beautiful head of black hair on the morning of the earthquake, and at 5 o’clock that same evening, his hair was white as snow from fright. I cannot vouch for this, but I believe the man told the truth.

The next day I visited some of the fine gardens in the city. These are mostly kept up by the French and English inhabitants of that city. They are very fine. All the enterprising people here are foreigners. The natives of this country are a very indolent and slothful race of people as a rule. Ten Americans can command double and triple the wages here that of a native. They tried hard to hire some of our men—blacksmiths and carpenters—offering them five and six dollars per day, but could not persuade any of them to stop off. [3]

To be continued…

I will post Nimrod’s journal in increments, but not necessarily every week.

[1] Nimrod Headington (1827-1913) was the son of Nicholas (1790-1856) and Ruth (Phillips) (1794-1865) Headington. He was born in Mt. Vernon, Knox County, Ohio, on 5 August 1827. He married Mary Ann McDonald (1829-1855) in Delaware County, Ohio, in 1849. Nimrod moved to Portland, Jay County, Indiana, by 1860 and a couple years later served in the 34th Indiana Infantry during the Civil War as a Colonel, Lieutenant Colonel, and Major. Nimrod died 7 January 1913 and is buried in Green Park Cemetery, Portland. Nimrod Headington is my fourth great-granduncle, the brother of my fourth great-grandfather, William Headington (1815-1879).

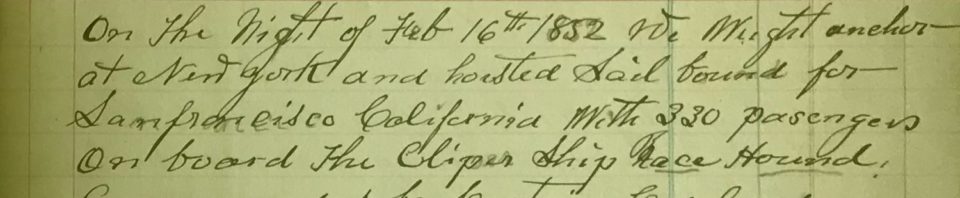

[2] Nimrod Headington at the age of 24, set sail from New York in February 1852, bound for San Francisco, California, to join the gold rush and to hopefully make his fortune. The Panama Canal had not been built at that time and he sailed around the tip of South America to reach the California coast.

Nimrod Headington kept a diary of his 1852 journey and in 1905 he made a hand-written copy for his daughter Thetis O. Tate. This hand-written copy was eventually passed down to Nimrod’s great-great-granddaughter, Karen (Liffring) Hill (1955-2010). Karen was a book editor and during the last two years of her life she transcribed Nimrod’s journal.

Nimrod’s journal, “Trip to California,” documents his travels between February of 1852 and spring of 1853.

[3] Nimrod Headington’s journal, transcription and photos courtesy of Ross Hill, 2019, used with permission.

2 comments

This diary is a treasure! It is wonderful to have such a rich contemporary account that conjures up this vivid picture of the city of Valparaiso at this time. Thanks for sharing this on your blog.

Author

It really is, isn’t it! Such a valuable resource and record of places and events from that time period. And there is more to come! Thanks for writing.